Historically, school gardens have been promoted by educational theorists and practitioners as sites for children’s experiential learning about and engagement with the natural world. School gardens can provide an organic space for learning within a natural and safe setting – a context that has been lost as traditional free play environments have been taken up by urban and suburban sprawl and in fears of physical and personal dangers to children. Through garden-based learning opportunities, children have shown academic and skills development, and deepened their ecological understandings of the impact of humans on the environment. School gardening projects have been able to open the school community to the knowledge, wisdom, and participation of families, elders, and local residents. Furthermore, research suggests that school gardening can positively influence children’s developing attitudes about and responsible actions in the environment. Planting Seeds for Change explored elementary school children’s experiences of their school garden and its findings highlighted the multiple ways of knowing and connecting to the garden and nature in the community and children’s early embodiments of a land ethic.

Research Design

Participating children were recruited from three classes at City Public School, a downtown school in Toronto: one grade 1 class, one grade 3 class, and one multi-grade junior ESL class. Children were required to provide both their own assent and parent/family consent in order to participate. In total, 43 children participated in the study.

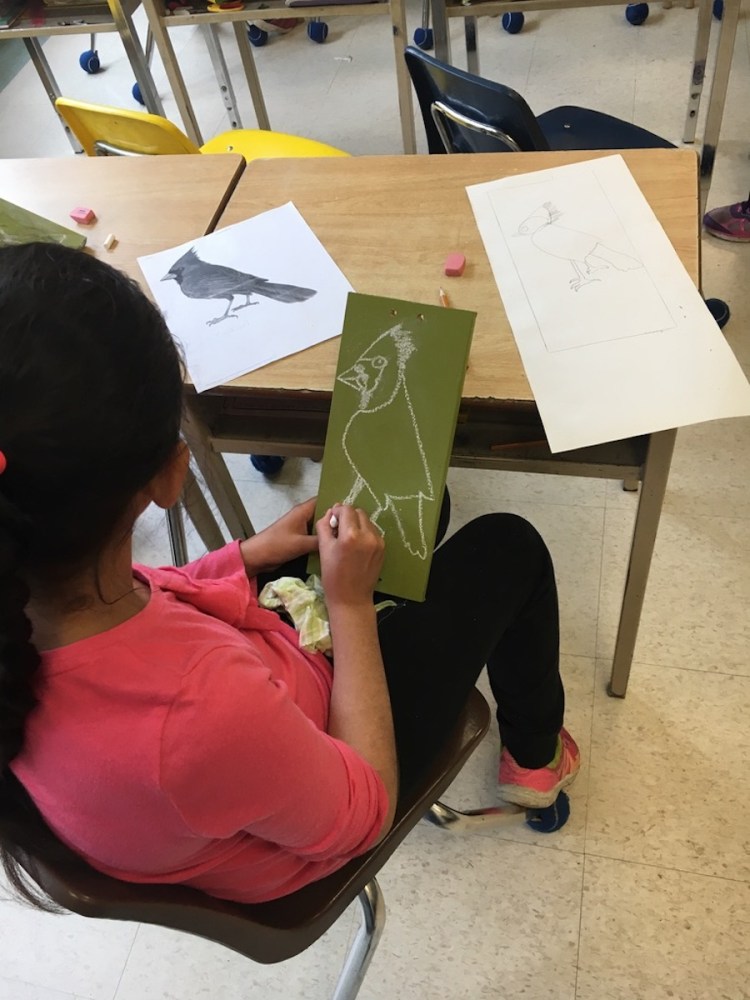

Data collected included observations and field notes, copies of children’s drawings and class work, audio recordings from garden-based activities, and photographs. Audio recordings were transcribed by the research team. The data were collated and analyzed together using qualitative thematic coding. While the identified themes are presented as separate findings, it is important to recognize that they are inextricably connected and overlapping in both the data collected from the children and in their school garden experience.

Themes in Children’s Experiences

Sensory Experience

Central to many of the children’s school garden experience was their sensory engagement with the plants and animals living there. The children experienced the garden’s colours, shapes, textures, sounds, smells, and tastes, and were excited to explore the garden in these ways. This was especially clear in children’s enthusiastic tasting of different plants grown in the garden; here, children eagerly sampled mint, lettuce, basil, lemon balm, chives, and kale as well as tea brewed from the garden’s herbs to name but a few. They compared the taste of produce that they grew in their school garden with the taste of food purchased at the grocery store. One grade 3 student asserted that “organic tastes more natural.” Children also related the tastes, smells, and visual features to other known plants: “[Parsley] tastes [like] a scent of tomato.”

Prior Knowledge and Experience

Children made many connections between the school garden and their prior knowledge and experiences. These included connections to curricular content learned in class and process skills including problem solving and scientific thinking. For example, on one visit to the school garden, a small group of grade 1 students predicted that a tulip without petals had been broken by someone visiting the garden or that it had melted in the warming temperatures. When looking at rhubarb with its long stalks and large leaves, some grade 3 students wondered if it might be an ancestor of celery and hypothesized that its oversized leaves were for collecting water.

Children also connected to earlier outdoor learning opportunities, both in the school garden and at local sites. A group of grade 1 students hypothesized that since it was not raining on their current visit to the school garden they would not see any worms because on their last rainy visit, they saw many worms coming up above the ground for fresh air. Grade 3 students noted that leaves in the garden smelled like those they smelled earlier in the year on a field trip to a large urban city park. Grade 3s also regularly referred to their gardening experiences with their school’s environmental club.

Personal Connections

Along with connections to prior knowledge and experiences related to curriculum and instruction at school, children also made frequent connections between their school garden and their own experiences with gardens, gardening, and cooking and eating with family and friends outside of school. Many children spoke about gardening with their parents, grandparents, and other family members, both in the city and in the suburbs. Several children connected the tastes and smells of garden herbs to cooking with their parents and eating with their families. Some children who were new to the school and to Canada spoke about their experiences with gardens and gardening in their home countries, including Japan, the Philippines, and Nepal.

Cause and Effect

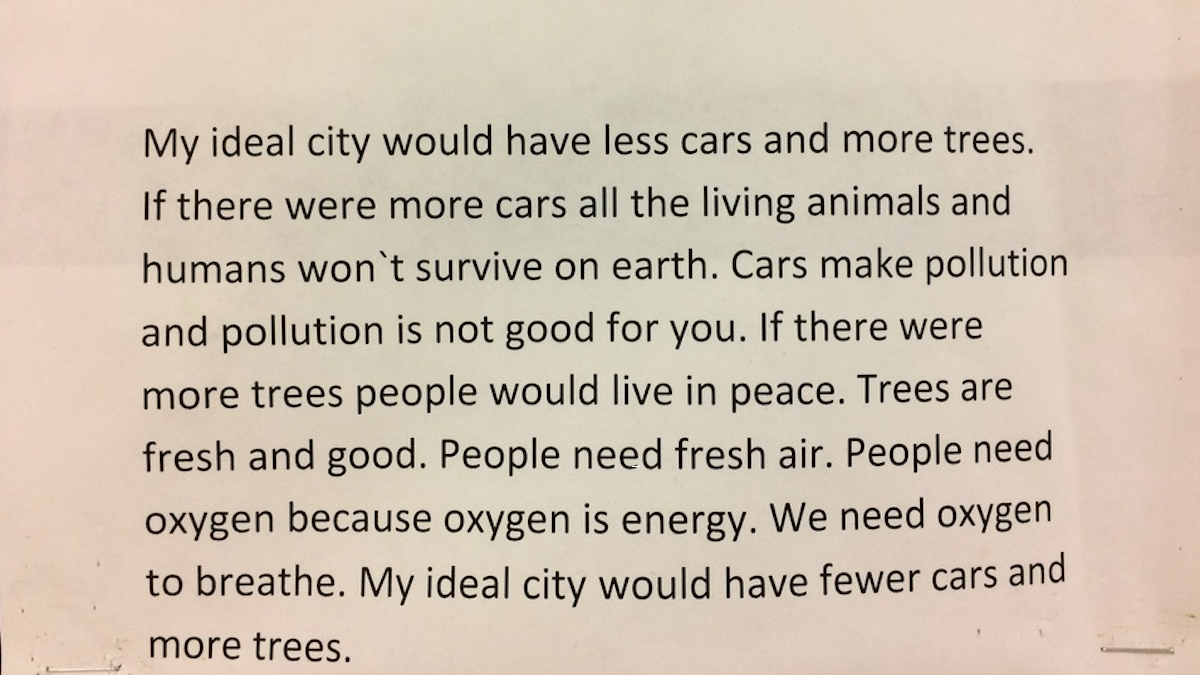

Children recognized the impact that humans and our life choices can have on the local environment and natural systems. Many of these connections were made explicitly by grade 1 students. These children spoke at length about the water cycle and the nearby river; for example, the impact on the water cycle of our reliance on gasoline, diesel, and fuels and the resultant acid rain was noted by children. Children discussed the historical practices of factories that dumped waste into local water systems: “The factory’s pollution went into the Don Valley River.” With the negative impacts shared, children also proposed possibilities for change. Specifically related to transportation, children asserted that we should not use gasoline-powered vehicles but should instead use electric and battery-powered vehicles and ride bicycles that “use muscles” for fuel. The children recognized how pollution impacts our health as it persists in our air and water cycles as “we breathe it in, we drink it in, and we eat it in,” and proposed that “when [they] grow up, [they] can put all of the pollution making away.”

Ecological Thinking

Children shared observations and understandings that allude to their development of ecological thinking. Making reference to many components and processes of their school garden, it was apparent that the children recognized the interconnectedness of plants, animals, and natural systems. The garden was identified as providing food for animals (bugs, spiders, bees, birds, caterpillar, ants, worms, and snails) and oxygen to allow us to breathe and live: “If you don’t have a garden, you won’t even have vegetables or fruit and you won’t survive.”

Children recognized the diversity of species living in the garden with even the youngest children listing many different plants and animals that lived there. The garden was seen to be an important part of the local ecosystem and a community of plants, fruits, vegetables, animals, and sunshine where “a community means all together as a world.” Along with understandings of the relationships between components of their school garden, grade 3 students also spoke about the natural and cultural relationships between the Three Sisters companion plantings of corn, squash, and beans.

Affect and Care

When discussing their school garden and nature in their community, the children showed that they cared about the natural world and that it was of value to them. The children thought it was important for their school to have a garden: “It’s a really good thing to have a garden in the middle of the city.” They also shared a sense of pride in having a garden. To them, the school garden was “cool” and some children thought that students from other schools might be jealous of their school garden. Children also voiced that the garden cared for them by feeding them and providing oxygen for them to breathe. One child told us of feeling sadness when a tree was cut down. Several children spoke about caring for the garden, particularly as part of their membership in the school’s environmental club.

A Developing Land Ethic

Taken together, the presence of the above themes in children’s discussions about and experiences of the school garden and nature in their community suggest that they are beginning to embody a land ethic. Here, they follow Aldo Leopold and this recognition of community as inclusive of all elements – soils, waters, plants, and animals – that make up the natural world. Children are also beginning to take up Leopold’s land ethic as they embrace a reciprocal and respectful relationship with the natural world and a changed role from “conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it” (Leopold, 1949/1966, p. 240). They acknowledge the importance of all members of our communities and the necessity of respecting the land and interacting with the land in a way that cares for its diversity and complexity: “We’re eco people … we wanna make the earth green.”

Acknowledgement

This research has been funded by a Toronto Metropolitan University Faculty of Community Services Seed Grant.