The urban school garden presents an oxymoron. It is a space of contradictions and disruptions and it is also an intersection opened for seemingly impossible possibilities. Historically, the urban environment is set apart from the natural environment. Likewise, school has been, and remains, bounded by curricular, institutional, and physical structures. In difference, the garden is an organic emergence that is full of life, growing beyond, beneath, and over the fences and borders that attempt to separate it.

Taken together, and following the unboundable nature of the garden, the urban school garden provides a motif for exploring and deconstructing epistemological binaries that frame our perceptions of curriculum, research, and representation in environmental education and in education more broadly in unique and unexpected ways. This project meditates on the experience of an urban elementary school garden through a year spent with and in the City Public School community.

Deconstruction as a Realization of Possibilities

Poststructural French philosopher Jacques Derrida has had an indelible impact across the humanities and social sciences, including the field of education. Derrida asserted that meanings are not fixed or universal; words are only signs that allow us to make meaning from experience and relate them to others so that we can better negotiate and understand our differences. This is something that we often take for granted today.

Deconstruction does not try to erase meaning in texts or discourse but rather opens meaning up to reveal the histories, stories, and identities that are already at work within them.

In educational research and practice, deconstruction and its re/opening of spaces and places to difference presents us with an ethical turn as multiple and marginalized voices and alternate texts are recognized and heard; it is here where deconstruction can contribute to environmental education research.

Research Design

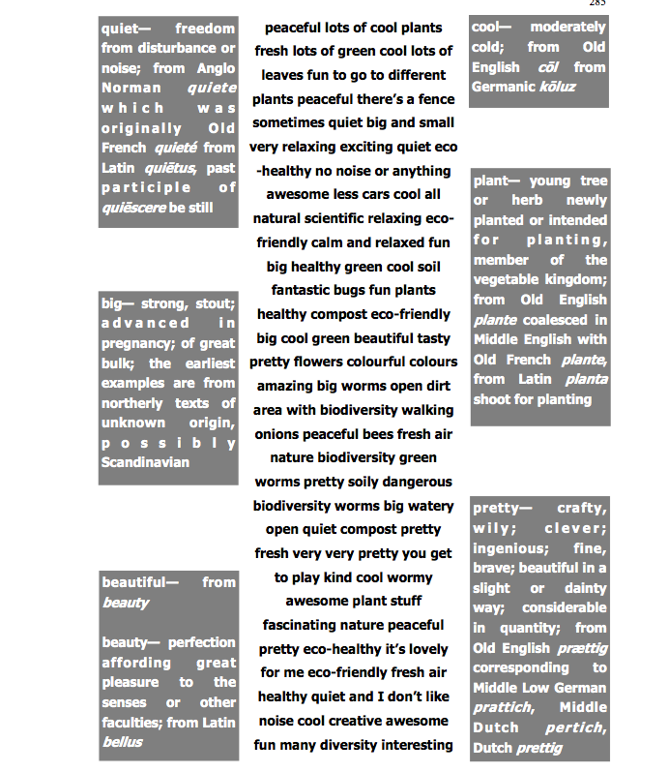

Rather than follow a set and singular methodology, this project draws from a range of approaches: narrative, ethnography, participatory research, and poststructural theory. The research space opened traces the experience of an urban elementary school garden and presents the story of a year spent with a grade 1, grade 3, and grade 6 class at City Public School. Along with day-to-day reflections, it shares the space of research opened by a school garden-related participatory research project done with a group of grade 6 students, the Cool Researchers, who were actively involved in all aspects of the research. The representation of the research itself plays with the flow of traditional academic writing, forgoing a singular linear form in favour of a text of multiplicity – one of columns, insertions, marginalia, images, and quotations – that is at once separate and always already connected and conversant.

Openings in Curriculum

Learning in and about the school garden blurred disciplinary distinctions, those subject areas so often ranked and ordered became obsolete. Instead, learning in and about the school garden was a decentering of the traditional curriculum that upset the dominance of mathematics, language arts, and science. This decentering opens a space for affect and action, for caring and caring for, and for what is not in the prescribed curriculum. The voices that echoed through this opening spoke not only of external frameworks and learning objectives, but also of internal connections, emotions, feelings, and ways that students felt cared for by the garden. And in return, students cared for the garden. Their connections to and their rootedness with and in the garden ran deeply; to the students of City, their school garden was an important, special place, a space that they cared for and that cared for them. The school garden created a unique opening within the framed and bounded institution of school for inter-actions with the natural world, with the community, with each other, and with the self.

The City school garden provided both content and context for learning across the curriculum. Sidney, a grade 6 teacher, stated that, “It’s not something you have to search for. You don’t have to … do backflips to get to the curriculum.” Students at City were learning about topics in science and mathematics through garden-based activities. They also used the garden as a context for learning in language arts, social studies, fine arts, and character education.

Their active involvement, and the hands-on, direct experience with the content and context of learning was not lost on the students. They too recognized, and appreciated, being able to learn about what is quite literally in their own backyard. The active doing was important for students. John Cena, a grade 6 student, said that in the garden, “You actually get to do something instead of just sit in your desk and write stuff.” For many, the garden motivated them to learn.

The school garden provided a shared space for building a sense of community, both within the school and more broadly. The older students, those who had been learning in the garden for years – who had in fact built several of the garden beds themselves – acted as mentors for younger students. ABPL, a grade 6 students, saw herself as a role model for her younger peers: “You’re kind of like a leader … little kids watch us … so if we are caring for plants, they think it’s right.” Students were able to model to their peers what they learned about the garden – how to care for it and the importance of caring for it.

Students at City also recognized the importance of working together to make positive change through their efforts in their school garden. TGTR, a grade 6 student, noted that in their efforts, “individuals won’t really make a big difference but people working together will make a big difference.” That said, students still acknowledged the importance of every little contribution to care for the garden and for the environment. Many spoke of steps that working in the garden had inspired them to take, from taking the straws out of their juice boxes before putting them in the recycling bin to picking up litter on the walk home from school.

Openings in Research

This project celebrates the inclusion of students as researchers, not only as subjects, in the research process through participatory action research, or PAR. PAR upsets the taken-for-granted relationship between researcher and researched. In educational research, and particularly with students as researchers, PAR further disrupts the binaries of teacher and student, teaching and learning, and expert and novice. By its active opening of the research space, PAR allows for a multiplicity of different ideas and voices to be heard. It is critical, reflexive, and transformative; it questions; it critiques practices, structures, and discourses often left unexamined; and it at once opens, grounds, and connects theory and practice. In this project, ten grade 6 students – the Cool Researchers – participated as co-researchers with Susan Jagger.

The Cool Researchers’ project focused on the school garden and they decided to explore:

- How do students experience the school garden?

- How do students feel about the school garden?

They discussed how they might find answers to their questions and they decided to collect data from a grade 3 and a grade 6 class with a written survey, school garden drawings, and small group interviews. After data was collected, they discussed the data together and sorted the data into groups of shared themes related to their research questions. Finally, the Cool Researchers presented their findings with teachers and school staff at City and with Susan at a graduate student research conference at OISE/University of Toronto.

How Do Students Experience the School Garden?

The Cool Researchers identified four ways that students experience the school garden: observing, learning, having fun, and caring. Students used all of their senses as they experienced the school garden; they tasted, smelled, touched, listened, and saw. Students also learned in the garden, and the Cool Researchers noted that students learned both what they called curriculum learning, which included science, mathematics, and art, and physical learning, which included planting, watering, digging, harvesting, and mulching. Students had fun in the garden as they played, discovered, researched, sketched, built raised beds and planters, and of course, ate vegetables, fruits, and herbs. Finally the Cool Researchers found that students experienced the garden by caring for the plants, the garden, the self, and the Earth. Mighty Robot, a grade 3 student, beautifully summed up the place of the garden at the school as both content and context for learning: “We go to learn in the garden and learn things about the garden.”

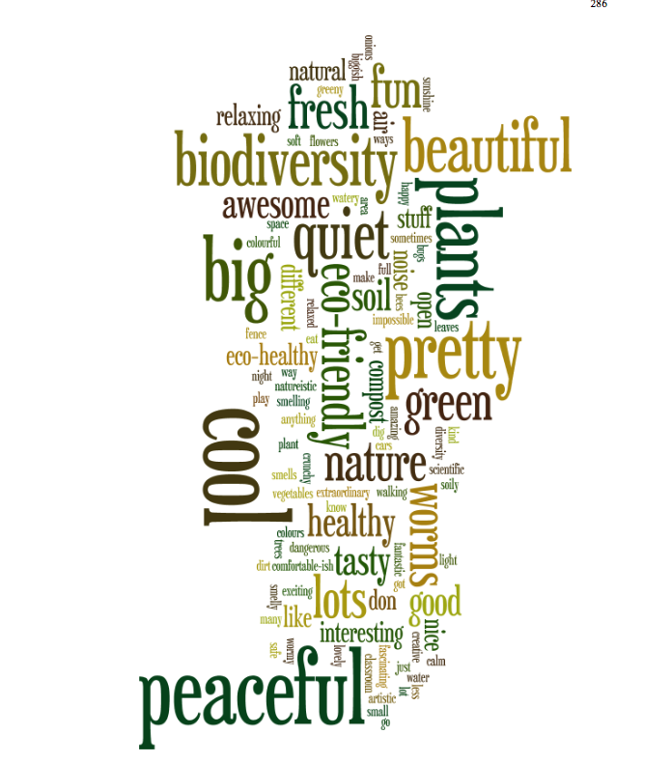

How Do Students Feel About the School Garden?

The Cool Researchers were surprised by the answers to this question; they did not anticipate the personal and reflective responses of their peers, some of whom were only 7 and 8 years old. Students identified the school garden as an escape from the noise and pace of both the school and the city. To the students, the garden was a place of calm and peacefulness and a place that they went to relax and get away from stress. They felt safe and comfortable in their school garden.

Maya, a grade 6 student, commented that for her, “it was like you get to take your mind away from stuff in the garden … There’s not stress and you don’t have to worry about stuff, like in real life.” For Maya, the garden was a place of refuge and this feeling was shared by many of her peers. The emotional and psychological benefits to children of time spent learning and being in the natural world were clear.

Openings in Representation

The textual re/presentation of the research is an extension of the opening and uprooting, and re-routing, of the research space that Susan was working in with the Cool Researchers. It re/presents the multiplicity and historicity always already within the research space. It was important to re/present this research in a way that mirrored the openness of the project itself – the opening of the curriculum and pedagogy to garden-based approaches and the opening of the methodology and methods to the participation and voices of students. Rather than bound the research with a linear text, the text would be a representational realization of deconstruction itself and of the multiple texts that can be traced throughout the research.

Postings of methodology, of philosophy, of history, of education, and of art inter-act, inter-sperse, inter-mingle with and in each other and with and in the stories, the images, the quotations, the comments of the research space, and of the research text. These include texts related to the children’s stories of their school garden experiences, garden-based pedagogies, the cultural history of gardens, participatory action research, the philosophical underpinnings of poststructuralism and deconstruction, and Susan’s analysis and critique of the texts themselves. And there is space as well, interruptions in the textual flow for play, for difference.

And so the re/presentation is one of multiple texts, woven together. Like poststructuralism, it does not attempt to erase the structures that came before but rather responds by opening the text itself to the realization of the complexity and multiplicity of perspectives that is always and already within the research and the research text.

The re/presentation responds to the often confining structures of the traditional research paper, the frames that enclose, and separate, the work. Its openness is a resistance to that bounding, upsetting the accepted, and so often unquestioned, architecture of the dissertation, and rejecting the possibility of a known, a transcendental signified. Instead, it embraces the flickering and endless chains of multiplicity, alterity, and difference in meanings made, connections traced, and understandings gained.